-

Character App Presentation

Character App Presentation Feb 28th, 2012 from maria maria on Vimeo.

Presentation Summary:

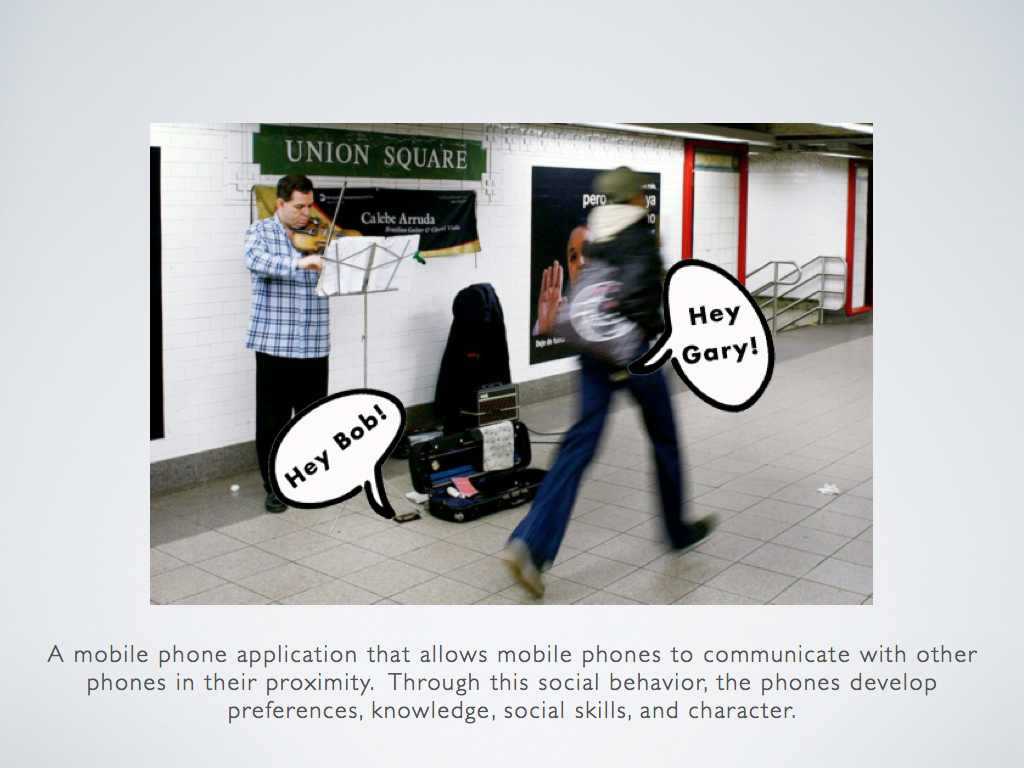

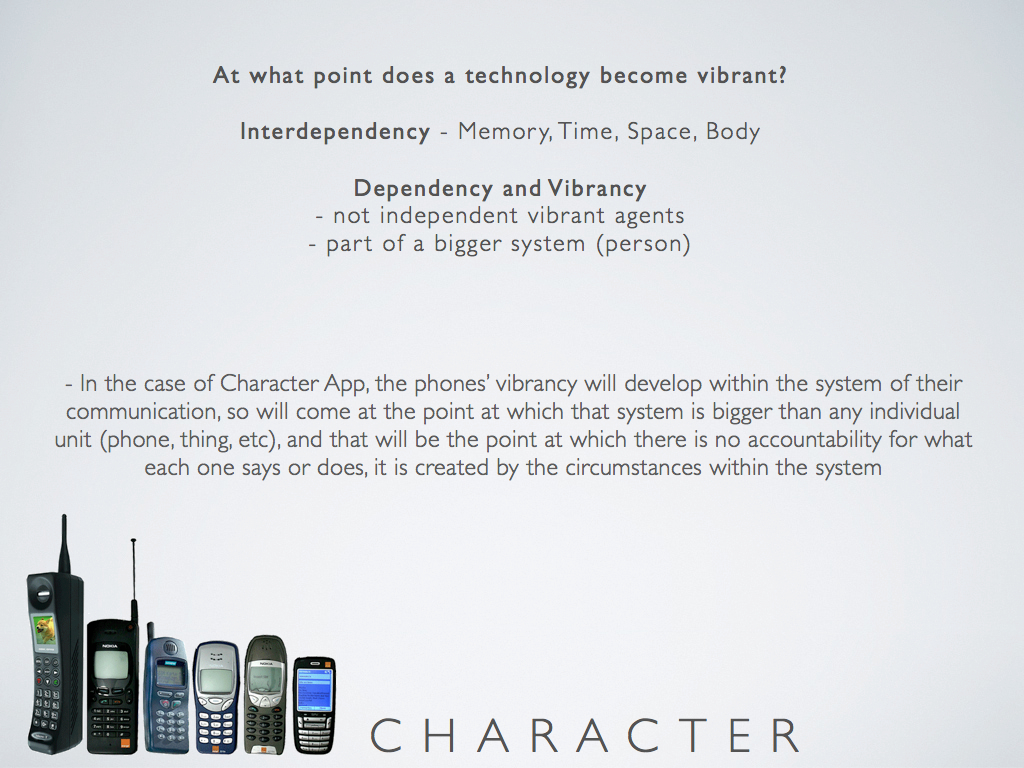

Character is a mobile phone application for Android that allows mobile phones to communicate with other mobile phones in their proximity. Through this social behavior, the phones develop preferences, knowledge, social skill, and character.

When they are interacting with other phones, the phones are able to speak out-loud to each other in human voices, introduce themselves, remember each other, develop relationships, learn from each other, and share information. Through these interactions they develp friendships as well as their own personalities.

At this point they have a basic Eliza/Chat Bot style conversation, but soon their initial conversations will also use information from a training set that incorporates basic knowledge of their system, their owner's data, information available on the internet, and information they learn from other phones that talk to.

The program uses NFC pairing to establish a connection. I recently decided to also incorporate bluetooth. NFC requires a very close distance, which is ok for initial pairing and recognition, especially because it allows for easy pairing not hindered by bluetooth's pairing protections. But NFC is not good for the phones sustaining a conversation at a greater distance. The nice thing that happens now, is that once phones are paired through NFC to bluetooth, they remain connected indefinitely. They can also maintain a conversation for a distance of around 10 feet.

I need to understand the mechanism better, and where in the settings each Android device controls this, but in my experience, the phones often remain paired even after being significantly separated for a while.

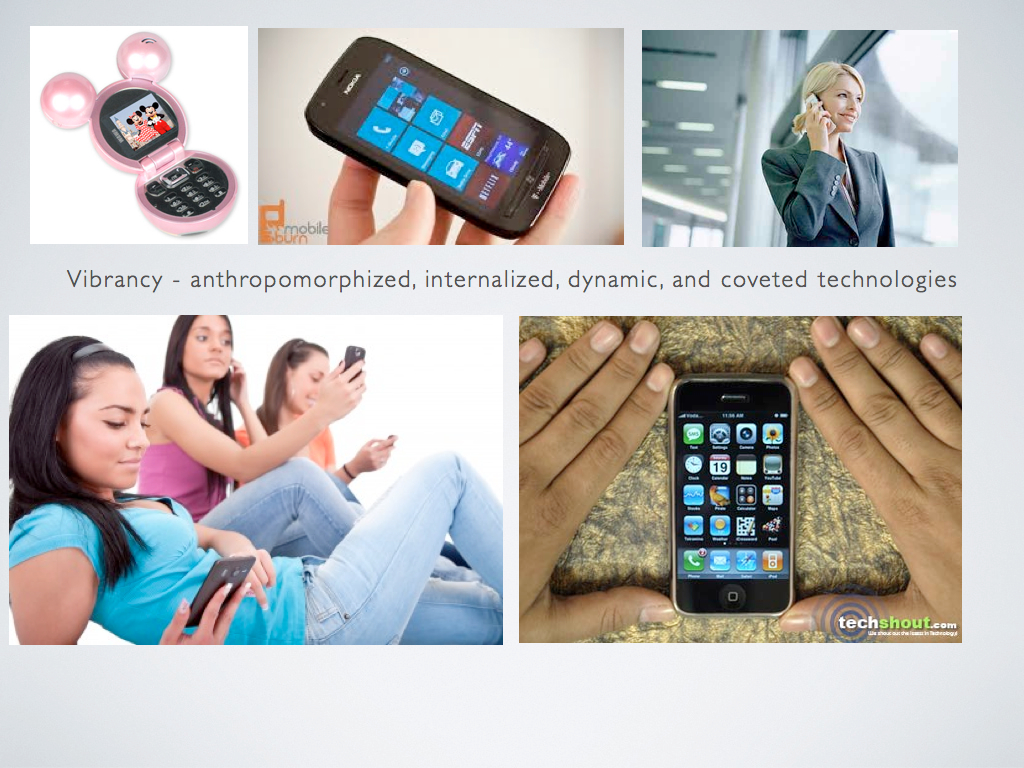

the Vibrant Mobile Phone: During the next few slides I will talk about my interest in mobile phones, and the type of vibrancy this application addresses.

Mobile phones are by now ubiquitous, as we have all noticed. Over the past ten to twenty years they have spread throughout the world, often bypassing, or leapfrogging, the landline systems that preceded mobile phones in the US, bringing long distance communications to people for the first time.

In the US, where landlines were long established and commonplace, and deeply embedded in culture, the mobile phone was first seen as an extension of the landline phone, a sort of extra-long-distance wireless home phone. Culturally this implied that the use of it still be restricted to private places, like the home, or a quiet corner. At first it was uncommon to see somebody loudly talking on their mobile phone, and it was advertised as something one should have in case of emergencies. I remember in mid-90s when most kids in middle school were starting to desire their own mobile phone, it was being advertised as a safety tool.

I point out this short-sightedness of the significance of the new technology, and the way in which it would transform every aspect of our lives, for two reasons. The first is that I think it is fascinating to try to imagine how the mobile phone entered the market and cultural mind set of places in Africa, Asia, and famously Finland in Europe, where by the mid 90s many households isolated from landlines had gone purely mobile. By the turn of the century, in many places in Asia, Africa, and the "developed" world, mobile phone use bypassed landline use. It is simply much more affordable to spread mobile use than it is to wire households to landlines. This is in addition to the fact that mobile phones are much more versatile. But in places where there was no landline precedent, their advantages came with the idea of long distance communication. This communication was immediately available from the individual, not based on a location-specific landline phone, but from your pocket. I find this really interesting because it frames the analysis I am about to make to being specific to the US and other places where landlines (and the psychological and cultural associations that came with them) predated widespread mobile phone use.

The second reason that I bring up the short-sightedness with which we welcomed mobile phones into our market, culture, and lives, is that this sort of short sightedness is the inevitable state of the present moment. We view all technologies (and everything else) in terms of the present cultural standards, and often fail to imagine their long term or peripheral consequences. The mobile phone was an enhanced and transportable home phone, great for emergencies. Now it is also a very small and portable camera that is conveniently always in your pocket, it is also a personal computer, a personal data storage, a health tool for some, a notebook, a flashlight, and many other things. But does that fact that we still consider it primarily a phone define the way we imagine how it has changed or will change our lives? Our view of technology? Our view of ourselves and our world? Also, does our view of it as an enhanced smaller version of all of these things get in the way of us seeing it as something completely new and different?

Today our mobile phone use is still somewhat modeled, psychologically or physically, on the landline system. We still rely on the same phone companies to provide us with communication services, wired and switched in some of the same physical locations that control our home phones. I wonder if this can change in light of the development of the Personal Area Network - with things like NFC and Bluetooth, and whatever is to come, as well as the ability to cary large amounts of data on your person, a new relationship to information in the cloud, and a new relationship to information in general. I wonder if reevaluating the technologies and their role in our lives can help us be more imaginative about their future, and our future with them.

It seems that sometimes technologies transform our culture and our sense of self without our noticing, despite the fact that in another view we create them to do these things. And there is a great deal of literature among men, mostly, I think, arguing for or against technological determinism, in various levels of abstraction. All of this is very important to the idea of vibrancy: does technology transform us, or do we control our destiny and use technology to do this. A current manifestation of this argument surrounds the "twitter revolutions" and the question of whether we owe the recent political movements to twitter and microblogging, or whether they just happened to be the current tool of choice for the same old process of political organization.

However, in discussing and reading about the idea of "vibrancy" in technology over the past few months (see reading list and sources here), I am beginning to view the issue as a relativist. In as much as everything can be viewed as a part of a greater system, depending on your scope of vision, technology seems to exist among us within a system of scale-dependent agency. There is more on this in another blog post in which I identify the vibrancy of mobile phones as being dependent on and defined on our reliance on them, which has had significant effects on the way that we live our lives.

In the next few slides I present an argument for the vibrancy of mobile phones by identifying some of the ways in which mobile phones seem vibrant, or seem to have agency. I do this by identifying three ways in which they are not just tools for us, especially not just tools for phoning people, but important parts of our lives. They have transformed our sense of time, our sense of space, our sense of our bodies and mids, and therefore our sense of self, in as much as the self is our mind, our memories, and our bodies.

TIME ::

In allowing us to constantly make short term adjustments to plans, and in allowing us to call ahead and say "I'm running late, can we meet at the coffee shop instead," for example, widespread use of mobile phones has dramatically changed the way we view time and our schedules. Time seems less static. Newer mobile calendar and time management software taps into this by allowing you to quickly delay and postpone events on your schedule, and to share your calendar with others. On one of my first mobile phones in the 90s, I had the option of selecting from a variety of generic messages when texting, to save me time. Most of them were along the lines of "I'm running late" or "I'm on my way" or "I'm not going to be able to make it" or "I can't talk now, call you later". Our ability to coordinate dynamically and reprogram each other's schedules on the go was one of the first major applications of the widespread use of mobile phones.

In his phd 2007 dissertation Mei-Po Kwan from Ohio State University, beautifully illustrated this concept through a metaphor to hypertext. In his metaphor, the new urban traveler views every moment of space and time as having possible connections to other people, places, or data via mobile communications devices. These connections are not defined by the traditional space of time progression and spacial distances, much like traditional reading, linear and sequential, has been transformed by hyperlinked reading, where every word can lead to a tangentially associated other text.

SPACE ::

His paper ties time and space together, as inevitably connected in our mind and our perception of the world as we move about it. In many ways the two are transformed together. There is another lens through which our sense of space, as it relates to communication and the phone, is undeniably transformed. And this, as I mentioned earlier, differs throughout the world dependent on the trajectory of land vs mobile phone use. In the US, and places with a similar history of landline use, we once associated the telephone with locations. We would call a landline, and expect to reach somebody at home, or at a public phone, or at a phone center. Today we usually start the conversation with "Where are you?," not knowing where we are calling, only who we are calling. The ability to call a person, instead of a place, is also the ability to disassociate people from space in a new way. A sense of dynamic reachable space is created around each person.

From the point of view of the person, a disassociation from context occurs. We are able to do more from where we are, and do not need to be anywhere in particular for some particular reasons. I no longer need to go home to retrieve my messages and make plans, and my entire life becomes rearranged. I spend more time traveling and less time at home. Many people are able to abandon traditional work/home space constraints. The idea of "the office" has changed drastically. Today it can mean a coffee shop, or a shared desk space, or a room in your home.

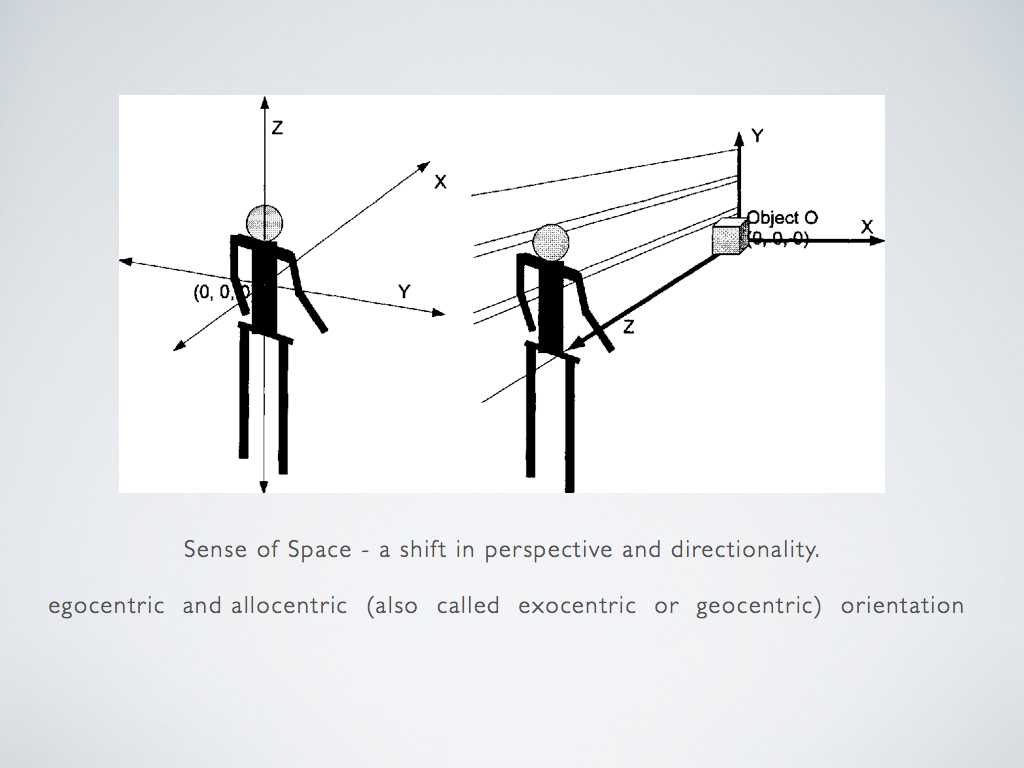

Our mobile devices also address directionality, and through the use of location services and gps mapping, give us a different view of the space around us. We no longer need to ask people how to get around, but have a satellite perspective on the space around us. We can use our map applications to guide us around the world, and tell us, with relative degrees of accuracy or success, the closest place to get gas, for example. Having this ability on your person is a big deal. It can fundamentally transform our view of the world.

Directionality is a significant political and social issue and may have interesting consequences. I know of two types of "directionality": egocentric and allocentric (also known as geocentric or exocentric).

Western cultures are predominantly egocentric. People tend to view direction from the point of view of themselves, with words like "right", "left", "up", and "behind", referring to those places in reference to your body, or self. "right" means to your right or myright. These directions depend on which way you are facing, not where you are in relation to the earth. In a few cultures around the world, most famously the Aborigines, directionality is expressed in terms of a geocentric view. One would not refer to yourright, but would say west of you or east of you, depending on your position on the earth, not the direction you are facing. In such cultures perception of position in relation to the world is significantly stronger.

It is difficult for me to even imagine being constantly aware of which way is east. And the fact that it is difficult to imagine is very important to my argument and ties back to the short-sightedness that defines our viewpoint of technology. Although it is difficult to imagine, allocentric directionality is possible and natural if you are accustomed to it. Our habits define our view of the world and of our sense of possibility. Our new ability to carry around a satellite view of the universe on our person will have implications on the way we view space. I am not sure what they are, but I believe they will be an amplification of our already egocentric views of space, and possibly an enhanced egocentricity in general.

Western cultures are predominantly egocentric in more ways than just spatially, and I don't know to what extent our spatial directionality is a symptom of this egocentricity, or to what extent it drives it. But our sense of space is a strong sense of orientation, influencing our behavior, our memories, and our other senses. It could, potentially, influence other aspects of our lives.

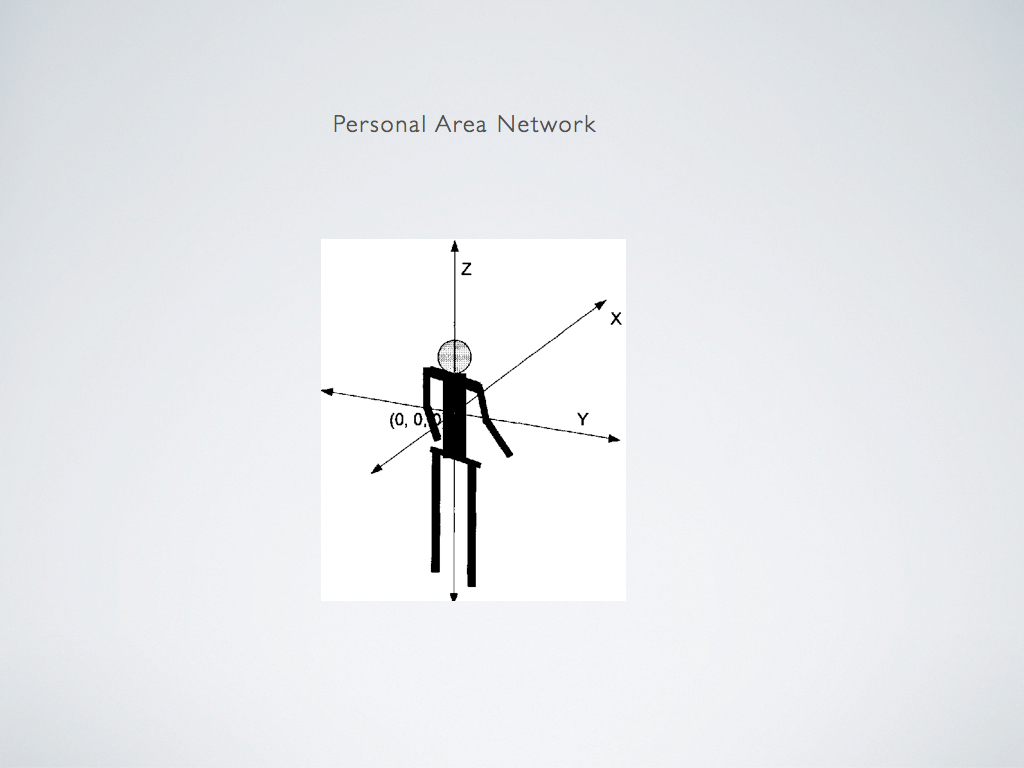

The Personal Area Network (PAN) is the local networking possibilities of a mobile device, including things like bluetooth and NFC (Near Field Communication). It seems to have a bright future in mobile computing and mobile phones, with many technologists getting excited about the possibilities of NFC, and the prospects of using it for passing information between collocated devices. Holding a satellite view of the world in your pocket can enhance your spatial perception, and it can give you a level of agency over your surroundings. The ability of mobile phones to share information, or to communicate directly with other phones in your proximity can give you the power to bypass traditional communication mediation by large telecomm operations. It raises your level of agency in that interaction by allowing you to control your own information flows. You can literally tap another phone to pass it information from your phone, instead of having to request that the information be passed through the towers, lines, or "series of tubes", controlled by your phone company, often at a price, and always at a risk of loss of privacy. Finally breaking away from these traditional structures and traditional telecomm corporations, may help to re-imagine mobile phones as more than just telephones, and to rethink their impact on our lives.

This is why I wanted to work with proximity triggered behaviors in the first place. Something about navigating and reacting to one's surroundings seem to suggest agency, perhaps it is by isolating the agent from the surroundings (in other words, simply by establishing a distinction, semantically or otherwise, between an "agent" and "surroundings", the agent is recognized).

SELF :: In the next few slides I talk about the way mobile technologies have transformed our sense of mind and body, and therefore our sense of self.

In another context I have been researching memory (you can see my notes here), and I discovered that the way we view memory has changed over time. For example, in education memory has gone from a vital component of education (alongside reason, logic, rhetoric in Rome and Greece) to something we question and often reject as a form of ineffective and wasteful learning that is not creative. For the Romans it was the essence of creativity. Without widespread availability of text and other resources, the building blocks of a person's creativity had to come from memory. Today we have such an abundance of text, web resources, and mobile resources, that the thought of memorizing everything you would want to include in your creative process is preposterous. These outside resources, also considered "cultural memory" or "shared memory" are a part of our creativity, and a part of our minds in a way unavailable to the memorizing Romans.

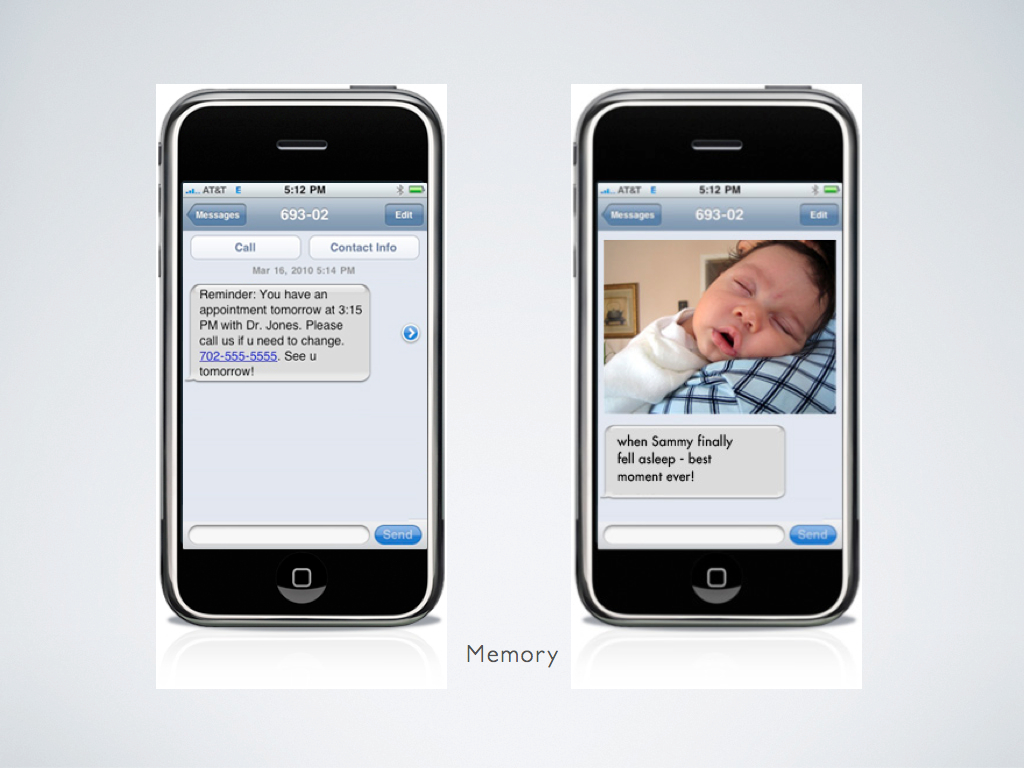

Other, more personal, memories, are also getting externalized. With the rise of the mobile phone we no longer need to remember any phone numbers, we put our notes, dates to remember, and directions, into the phone. We even take photographs of moments or places we would like to remember, and store them on our mobile devices, uploading them to our blogs, sending them via email, etc. Our personal memories are being externalized. In this way the mobile device has become a mental appendage, a part of our memory system.

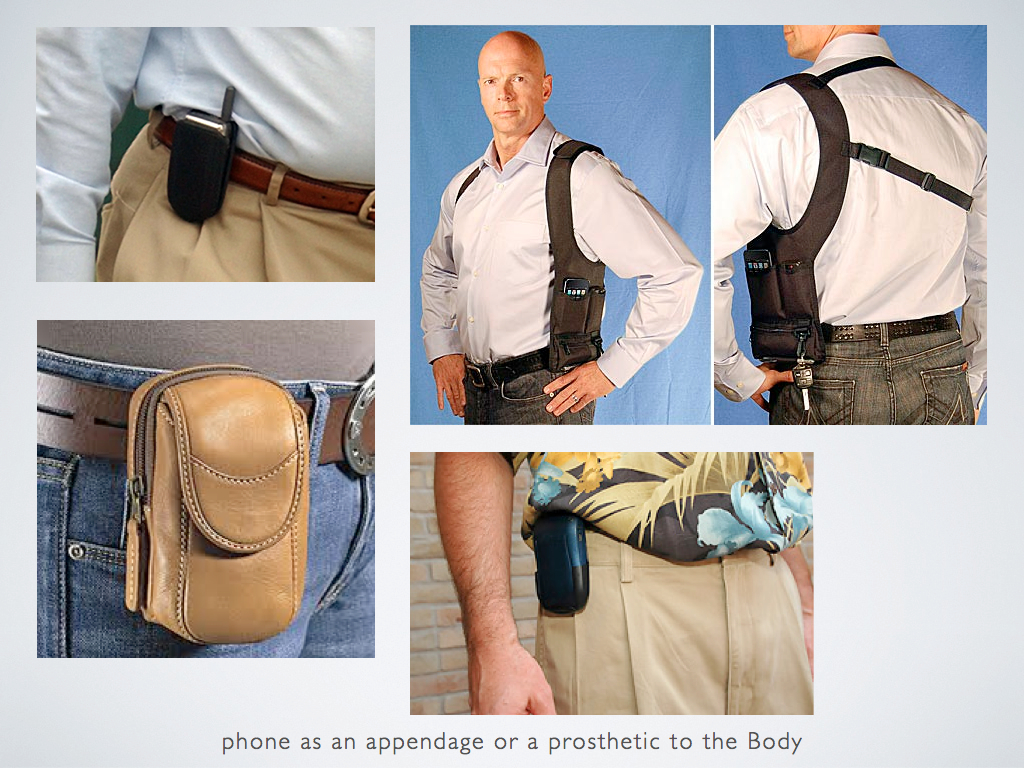

In a similar way, it has become a part of our body. The picture below says it all, so I will not elaborate too much. In as much as they can be incongruent to our bodies, as I described before, we do hold on to them throughout the day, fit them in our pockets, design pockets specifically for them, and create cell phone holders, arm bands, headphones, and ear pieces to seamlessly integrate the devices to our bodies.

In between the mind and body is an emotional connection with the phone. Like the carpenter who feels pain when his hammer is hit, we can feel fear or pain in that moment when our cell phone, which has slipped from our hand, is plummeting toward the ground. As it splatters, with its battery and case spreading on the floor, we can feel shock and anticipation as we put it back together. Their monetary value, the value of memories stored on them, and their practical value as tools for communication and information retrieval contribute to their overall value as a part of ourselves.

There is also a value in the device as it is seen and accepted in the cultural perspective. It can be seen as a tool of power and it can be used as a symbolic communication device. For example, it can be used outwardly to communicate that you are popular, or that you have the ability to call for help. The photos below illustrate the phone as a comfort device, and a defensive protective device that can say to people "I am not interested, and I am not alone, I am busy, do not talk to me." Phone use via symbolic displays was beautifully studied by Dr. Sadie Plant in her ethnographic study for motorola. Now probably in need of an update, since it is 10 years old, the study is still very entertaining and illuminating.

Plant discusses some gender dynamics that can be observed through mobile phone use and mobile phone display that are truly remarkable and I recommend reading. The images below illustrate what I think she called using the phone for "psychosexual innuendo".

The next few slides I try to illustrate the ways in which we have adapted to the touch screen interface.

Mizuko Ito, in "Personal, Portable, Pedestrian" talks about the "thumb generation" in Japan, a generation of young people that, due to the widespread use of texting and mobile games, use their thumbs for things that previously were always done with the index, or pointer finger: things like pointing and ringing doorbells.

The touchscreen interface tries to make navigation natural, and in many ways the motions we use are intuitive. Still using these gestures on the tiny devices, the kinds of body movements this entails, the change in posture it encourages, and the other physical manifestations of the interface can seem funny and awkward. It creates moments where this union between the person and the device can be studied in a new way. Certain motions that were new can become a part of our lexicon and cultural norm.

New devices can lead to new views of our bodies, new ways of using our minds, and new ways of communicating with each other and the world, both through new perspectives, and through new physical and language habits.

Our willingness to learn and get to know our devices and the ways in which they need to be touched speaks to our relationship to them within the person-device relationship that I am addressing.

There is a mutual dependency within our relationship to our devices. They need us for existence, for their power, and for the power they have as tools have that stems only from our use of them. They rely on us to move around the world, to gain access to networks, and to information, and to gain new capabilities, as through apps we install on them, for example.

We rely on them in all of the ways that I have described above, like memory, navigation, communication, scheduling, note taking, etc. The more information, networks, and functionalities that we introduce them too, the more powerful tools they become, and the more we rely on them.

This person-device relationship is reflected in our interactions with the device. And, as Sadie Plant pointed out, this interaction reflects who we are as people, as well as the devices we use. In the study I mentioned above, she identified different styles of device use that reflect different personality types. In as much as the device dictates the way we use it, we also adapt our use of it to our personalities. The image below shows an introvert and an extrovert using the phone in their unique styles.

I would like to conclude that the vibrancy I am addressing in mobile phones stems from our use of them, and our incorporating them into our lives. They have fundamentally transformed us, in the way we view our time, our space, and ourselves, and have therefore become indispensable components in our lives (to different extents of course). In this way, that have become components of a system, the person-device system, that is greater than the sum of its parts. Agency, traditionally ascribed to the person, becomes shared, within this system, with the device, therefore imbuing the device with a level of agency.

Right now my Character Application seeks to bring awareness to this phenomenon by anthropomorphizing the phone, and giving it an unexpected form of agency. In doing so, the user's sense of what the phone is for is questioned and brought to light. Our expectations, when thwarted, can help us understand the scope of our views, short-sighted or not. I don't want to make any value judgements, but to ask questions and experiment with new roles for the technology. As I continue to work on this application, I am interested in what other possible uses for this sort of agency, or vibrancy, could be. I would like to experiment with this once the program is ready for deployment. In the long run, I am would like to explore if through applying this process to interaction design via trying to give programs more personality, or allowing phones to develop a personality congruent to the users, as their relationship develops, it could become less symbolic, and more practical.